The latest Romaine lettuce outbreak: Just say no.

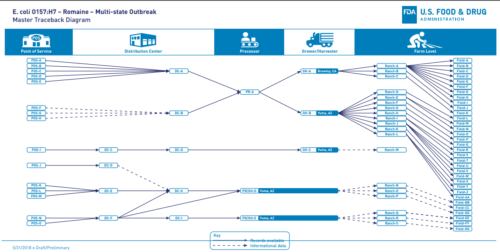

The CDC continues to track the latest outbreak of illnesses caused by eating Romaine lettuce contaminated with E. coli O157:H7.

The outbreak at a glance:

- Reported Cases: 67

- States: 19

- Hospitalizations: 39

- Deaths: 0

- Recall: Yes

Consumers should not eat romaine lettuce harvested from Salinas, California. Additionally, consumers should not eat products identified in the recall announced by the USDA on November 21, 2019.

A former FDA official, Stephen Ostroff, says:

With five multistate outbreaks in less than two years, it’s clear there’s a serious continuing problem with E. coli O157:H7 and romaine lettuce. The natural reservoir for this pathogen is ruminant animals, especially cattle. Moreover, one particular strain of E. coli seems to have found a home in the growing regions of central coastal California, returning each fall near the end of the growing season.

It’s not clear where this strain is hiding. Cattle? Water sources? Elsewhere? What is clear is that additional steps must be taken to make romaine safer.

The New Food Economy emphasizes some particularly distressing aspects of this particular outbreak.

- It is caused by the same strain of E. coli O157:H7 that caused outbreaks linked to leafy greens in 2017 and to Romaine lettuce in 2018.

- This strain of E. coli seems particularly virulent: 39 of the 67 cases had to be hospitalized.

- The source has not yet been traced.

People should avoid all romaine lettuce and that any currently in refrigerators should immediately be thrown out because of the risk of E. coli contamination…CR’s experts think it is prudent and less confusing for consumers to avoid romaine altogether, especially because romaine is also sold unpackaged and in restaurants, and customers can’t always be sure of the origin that lettuce. “Much of the romaine lettuce on the market at this time of year is from Salinas,” says James E. Rogers, Ph.D., director of food safety research and testing at Consumer Reports.

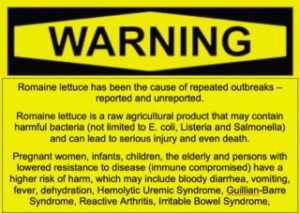

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler says enough is enough; It’s time to put warning labels on Romaine lettuce.

Marler’s advice: when in doubt, throw it out.

My comment: Contamination of vegetables with toxic E. coli means that the vegetables somehow came in contact with waste from farm animals or wild animals or birds. The most likely suspect is Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) or large dairies because they produce so much animal waste. If one animal is infected under crowded CAFO conditions, other animals also will be infected (but cows don’t show symptoms).

Preventing lettuce contamination means that CAFOs must manage their waste so that it is not infectious (USDA and EPA regulated) and vegetable farms must keep infected water from contaminating their crops (FDA regulated). All of this means following food safety procedures to the letter, but also in spirit.

Constant Romaine outbreaks are further evidence for the need for consistency in USDA and FDA food safety policies, and a reminder that calls for a single, united food safety agency have been coming for more than 40 years. Surely, it’s time.