Front-of-package labels: a survey and reprise

Food Navigator’s “special edition” on front-of-package labeling includes the results of a new survey of readers’ attitudes and a round up of previous articles.

Front-of-pack poll results: No clear winner (except cynicism…): The results of this poll are amusing, not least because they depend—as always—on how the questions were asked. Respondents to this one were offered five choices:

- Facts up Front. Consumers don’t want to be told what to eat (29% picked this one).

- The IOM scheme. Busy shoppers need more guidance (19%).

- Other points-based schemes that include positive nutrients. eg. Guiding Stars (11%).

- Traffic-light-type color-coding schemes (~5%).

- We’re kidding ourselves if we think front-of-pack labels will change behavior (36%).

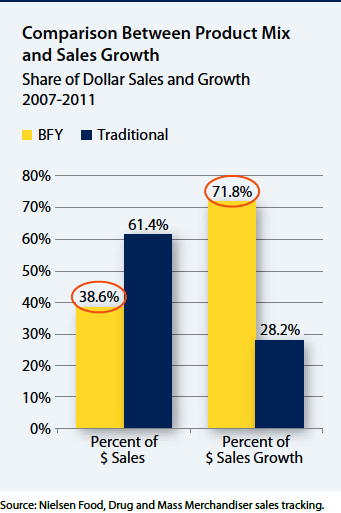

This last is tempting. Front-of-package labels, as I keep insisting, are about encouraging sales of one processed food product over another. They have little to do with encouraging healthier food choices.

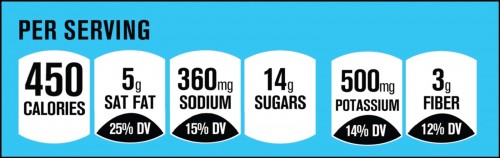

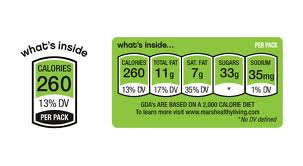

Front-of-pack labeling in pictures: Healthier choices at a glance or more nutritional wallpaper?: Red lights, green dots, ticks, stars, healthy seals, nutrients to encourage, nutrients of concern, smart choices… The aim of front-of-pack labels is simple – to help us make healthier choices (or at least more informed ones) – fast. But how best to achieve this has prompted a storm of controversy on both sides of the Atlantic….

IOM front-of-pack labels are step in right direction but need more work, says Guiding Stars advisor: The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) proposed front-of-pack (FOP) labeling scheme is a positive step forward, but “needs much more work”, according to supporters of one leading FOP scheme already up and running in the marketplace….

IOM front-of-pack labeling scheme: It’s bold, it’s simple and I love it. But is it fair?: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) certainly didn’t pull any punches in its front-of-pack labels report yesterday….

IOM calls for ‘fundamental shift’ in approach to front-of-pack food labeling: Front-of-pack (FOP) labeling schemes should “move away from systems that mostly provide nutrition information without clear guidance about healthfulness and toward one that encourages healthier food choices”, according to a high-profile report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM)….

Not a word from the FDA about the IOM’s front-of-package report. What will FDA do? What can FDA do? It’s a voluntary scheme and companies can voluntarily refuse to use it. Hence: those useless (except to food companies) “Facts Up Front.”