GMO’s Decoded is a gift to anyone confused about genetically modified foods. In this latest addition to Sheldon Krimsky’s prolific output of books about how societies interact with new technologies, he takes on a formidable challenge–to examine the science of GMOs as a basis for dealing with the ferocious politics they incite. I use “ferocious” advisedly. Positions about GMOs appear polarized to the point of outright hostility. Krimsky wants détente. If we understood the science better, we might be able to achieve more nuanced views of the risks and benefits of GMOs and of the genetic techniques used to create them.

To anyone familiar with Krimsky’s previous and ongoing work, this book may come as a surprise. Trained in physics and philosophy, Krimsky is a sharp critic of the role of technology in society with particular interests in the ethical implications of genetics and biotechnology and in risk communication. I have long admired his work for its firm grounding in science and its clear delineation of the ways in which political, cultural, and other societal factors color perceptions of the safety and other risks of new technologies.

In GMO’s Decoded, Krimsky takes a deep dive into the science of food biotechnology on its own, separate from issues related to how the science is used by the companies producing and profiting from GMOs, or is interpreted by proponents, critics, or the general public. An attempt to discuss the science of GMOs distinct from its politics may appear foolhardy, if not impossible, and Krimsky deserves much praise for taking this on.

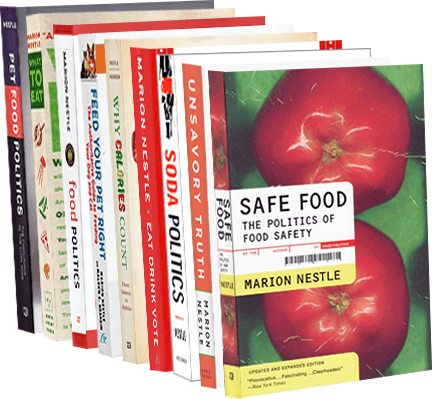

I speak from experience. My book about food biotechnology, Safe Food, first published in 2003, began with a reference to C.P. Snow’s two-culture problem—what Snow called the “gulf of incomprehension” between scientists and nonscientists over matters of technological risk. To greatly oversimplify: scientists argue that if GMOs are safe, they are fully acceptable and no further criticism is justified. But to nonscientists, safety is only one of many concerns about GMOs and not necessarily the most important. Holders of this broader view argue that even if GMOs are safe, they still may not be acceptable for reasons of ethics, social desirability, unfair distribution, nontransparent marketing, or inequitable and undemocratic control of the food supply.

What I observed in discussing those issues, and continue to observe, is the discounting of anything other than safety by extreme proponents of GMOs who perceive even the slightest question about nonsafety issues as an attack on the entire industry. This has forced critics of GMOs to focus on safety issues rather than the far less quantifiable issues of social desirability, pushing critics into positions that deny the possibility of any benefit of GMOs. The result: Snow’s gulf of incomprehension.

Is the gulf bridgeable? Krimsky argues yes. From the perspective of the science, GMOs can either benefit or harm society. It behooves us all to try to understand what the science is about as a basis for coming to more informed opinions about the uses, value, and risks of GMOs—the politics.

But before getting to what Krimsky does in this book, I want to make one point about GMO politics: the GMO industry brought the polarization on itself. As I explained in Safe Food, the first GMO food, the FlavrSavr tomato, was intended to be marketed transparently as a triumph of American technological achievement (I still have itss label in my files). British supermarkets sold tomato paste prominently labeled as genetically modified without opposition. That changed under industry pressure for nondisclosure. I was a member of the FDA’s Food Advisory Committee in 1994 when the agency ruled against labeling GMOs, despite evidence that trust requires transparency. The GMO industry fought labeling then, and won, and continues to spend fortunes fighting labeling.

The industry also promised that food biotechnology would feed the world and create new foods that would solve problems for the developing world, such as those able to withstand poor soil conditions, excessive heat, and limited water. But instead, the industry concentrated on far more profitable insect- and herbicide-resistant first-world crops, a strategy criticized for the effects on society of its monoculture, patented seeds, heavy use of herbicides, herbicide-resistant weeds, and destruction of beneficial insects. The potential for foods with consumer benefits remains, but has been largely unrealized. Trust requires fulfilled promises.

As readers of Krimsky’s previous books surely know, he cares about such issues and others related to the politics of GMOs and their societal impact. But in this book, he wants readers to realize that the risks and benefits of GMOs depend on understanding the state of their science. Here, he takes on the scientific questions, one by one, clearly and dispassionately. This must have taken courage and a great deal of work. The science of GMOs is complicated and occurs at the level of molecules–DNA, RNA, and protein, of course, but also a host of less familiar molecules responsible for making genetic modifications work.

Fortunately, Krimsky writes clearly and succinctly about such things, his descriptions are easy to follow, and he defines terms as they are needed. He begins by asking whether GMOs differ from foods produced by traditional breeding and if they do, whether the differences matter. He wants to know how GMOs affect health and the environment, whether they really are more productive than conventional crops, and whether they use fewer pesticides and herbicides. He asks whether they GMOs have nutritional or other benefits for consumers, and whether and how they should be labeled. He deals with these questions in short chapters, along with others, that examine methods and risk assessment, review what expert committees say about such matters, and use Golden Rice as a case in point.

Krimsky’s presentation of the divergent viewpoints about what the science means is exceptionally fair and even-handed. He insists that:

“This book is not about taking sides. My experience in studying scientific controversies that have public policy implications is that there are often truths, falsehoods, exaggerations, assumptions, fear-mongering, and uncertainties in the claims found on multiple sides of an issue. This book will succeed if it…demystifies the science and shows where there is consensus, honest disagreement, or unresolved uncertainty. ”

I think it succeeds admirably. Krimsky is straightforward about his own assessments. For example–spoiler alert—he concludes that evidence supports a qualitative difference between traditional and molecular breeding of food plants. On other questions, when he assesses the science as inconclusive, he says so. He wants readers to understand the complexity of the scientific issues, to be skeptical of arguments from either extreme in the debates, and to adopt nuanced positions on GMOs. Some aspects of GMOs may be worth opposing, but some may well be worth promoting. We all need to know the difference.

Krimsky tells us that in researching this book, his own positions became less polarized and more nuanced. Reading it, mine did too. Now it’s your turn.

–Marion Nestle, New York, August 2018