Another five industry-funded studies with sponsor-favorable results. The score: 145/12

Thanks to a reader for sending these items from a journal that I don’t usually come across. These bring the casually collected total since last March to 145 studies favorable to the sponsor versus 12 that are not.

Consuming the daily recommended amounts of dairy products would reduce the prevalence of inadequate micronutrient intakes in the United States: diet modeling study based on NHANES 2007–2010. Erin E Quann, Victor L Fulgoni III and Nancy Auestad. Nutrition Journal 2015; 14:90 DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0057-5

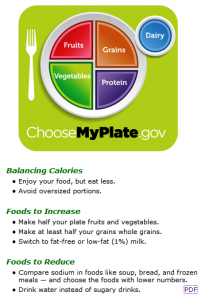

- Conclusion: Increasing dairy food consumption to recommended amounts is one practical dietary change that could significantly improve the population’s adequacy for certain vitamins and minerals that are currently under-consumed, as well as have a positive impact on health.

- Funding: The study and the writing of the manuscript were supported by Dairy Management Inc.

Association of lunch meat consumption with nutrient intake, diet quality and health risk factors in U.S. children and adults: NHANES 2007–201Sanjiv Agarwal, Victor L. Fulgoni III and Eric P. Berg. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:128. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-011f8-9

- Conclusions: The results of this study may provide insight into how to better utilize lunch meats in the diets of U.S. children and adults.

- Funding: The present study was funded by North American Meat Institute.

A review and meta-analysis of prospective studies of red and processed meat, meat cooking methods, heme iron, heterocyclic amines and prostate cancer. Lauren C. Bylsma and Dominik D. Alexander. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:125. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0111-3

- Conclusion: Dose-response analyses did not reveal significant patterns of associations between red or processed meat and prostate cancer….although we observed a weak positive summary estimate for processed meats.

- Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), a contractor to the Beef Checkoff. NCBA did not contribute to the writing, analysis, interpretation of the research findings, or the decision to publish…LCB and DDA are employees of EpidStat Institute. EpidStat received partial funding from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA), a contractor to the Beef Checkoff, for work related to this manuscript. The conceptualization, writing, analysis, and interpretation of research findings was performed independently.

Are restrictive guidelines for added sugars science based? Jennifer Erickson and Joanne Slavin. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:124. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0114-0

- Conclusion: However, there is currently no evidence stating that added sugar is more harmful than excess calories from any other food source. The addition of restrictive added sugar recommendations may not be the most effective intervention in the treatment and prevention of obesity and other health concerns.

- Disclosure: Jennifer Erickson, is a PhD student in Nutrition at the University of Minnesota working with Dr. Joanne Slavin. Joanne Slavin is a professor in the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota. In the past 5 years, she has given 150 scientific presentations in 13 countries. Many of these meetings received sponsorship from companies and associations with an interest in carbohydrates and nutritive sweeteners…Her research funding for the past 5 years has included grants from General Mills, Inc., Tate and Lyle, Nestle Health Sciences, Kellogg Company, USA Rice, USA Pears, Minnesota Beef Council, Minnesota Cultivated Wild Rice Council, Barilla Company, USDA, American Egg Board, American Pulse Association, MNDrive Global Food Ventures, International Life Science Institute (ILSI), and the Mushroom Council. She serves on the scientific advisory board for Tate and Lyle, Kerry Ingredients, Atkins Nutritionals, Midwest Dairy Association and the Alliance for Potato Research and Education (APRE). She holds a 1/3 interest in the Slavin Sisters Farm LLC, a 119 acre farm in Walworth, WI.

Cow’s milk-based beverage consumption in 1- to 4-year-olds and allergic manifestations: an RCT. M. V. Pontes, T. C. M. Ribeiro, H. Ribeiro, A. P. de Mattos, I. R. Almeida, V. M. Leal, G. N. Cabral, S. Stolz, W. Zhuang and D. M. F. Scalabrin. Nutrition Journal. 2016;15:19. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-016-0138-0

- Conclusion: A cow’s milk-based beverage containing DHA, PDX/GOS, and yeast β-glucan, and supplemented with micronutrients, including zinc, vitamin A and iron, when consumed 3 times/day for 28 weeks by healthy 1- to 4-year-old children was associated with fewer episodes of allergic manifestations in the skin and the respiratory tract.

- Funding: This study was funded by Mead Johnson Nutrition…The study products were provided by Mead Johnson Nutrition. Dr. Scalabrin, S. Stolz, and W. Zhuang work in Clinical Research, Department of Medical Affairs at Mead Johnson Nutrition. All of the remaining authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Ann M. Albertson, Marla Reicks, Nandan Joshi and Carolyn K. Gugger. Nutrition Journal 2016;15:8. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-016-0126-4

- Conclusions: The data from the current study suggest that greater whole grain consumption is associated with better intakes of nutrients and healthier body weight in children and adults. Continued efforts to promote increased intake of whole grain foods are warranted.

- Competing interests: Marla Reicks received an unrestricted gift from the General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition during the manuscript preparation to support research at the University of Minnesota. Carolyn Gugger and Nandan Joshi are current employees and stockholders of General Mills, Inc. Ann Albertson was an employee of General Mills, Inc during the conception, analysis and initial preparation of the manuscript. She is currently retired from General Mills.

- Non-financial competing interests: General Mills, Inc is a global consumer foods company that manufactures and sells products across a broad variety of food categories, including grain-based foods. General Mills product portfolio includes ready-to-eat cereals, cereal bars, baked goods, flour, and salty snacks that may contain whole grain.