My latest publication is a commentary on the reversal of the Danish fat tax in New Scientist, November 26:

Fighting the flab means fighting makers of fatty foods

A YEAR ago in these pages, I congratulated the Danish government on its revolutionary experiment. It had just implemented a world-first fiscal and public health measure – a tax on food products containing more than 2.3 per cent saturated fat.

This experiment has now been dropped. Under intense pressure from the food industry in an already weak economy, the Danish government has repealed the fat tax and abandoned an impending tax on sugars.

Nobody likes taxes, and the fat tax was especially unpopular among Danish consumers, who resented having to pay more for butter, dairy products and meats – foods naturally high in fat.

But the real reason for the repeal was to appease business interests. The ministry of taxation’s rationale was that the levy on fatty foods raised the costs of doing business, put Danish jobs at risk and drove customers to buy food in Sweden and Germany.

In June this year, a coalition of Danish food businesses organised a national repeal-the-tax campaign. The coalition said that fat and sugar taxes would cause the loss of 1300 jobs, generate high administrative costs and increase cross-border shopping – precisely the arguments cited by the government for its U-turn.

We can now ask the obvious questions. Did the tax achieve its aims? Was it good public policy? What should governments be doing to reduce dietary risk factors for obesity?

The purpose of food taxes is to reduce sales of the products concerned. In bringing in its fat tax, the Danish government also wanted to raise revenue, reduce costs associated with obesity-related diseases, and increase health and longevity. A year is hardly time to assess the impact on health, but the tax did bring in $216 million. Danes will now face higher income taxes to make up for the loss of the fat tax.

Business groups insist that the tax had no effect on the amount of fat that Danes ate, although they chose cheaper foods. In contrast, economists at the University of Copenhagen say Danish fat consumption fell by 10 to 20 per cent in the first three months after the tax went into effect. But it is not possible to know whether it fell, and cross-border shopping rose, because of the tax or because of the slump that hit the Danish economy.

A recent analysis in the BMJ suggests that 20 per cent is the minimum tax rate on food to produce a measurable improvement in public health. The price of Danish foods hit by the tax increased by up to 9 per cent, enough to cause a political firestorm but not to make much of a difference to health.

Is a saturated-fat tax good public policy? A tax on sugary drinks would be a better idea. To see why, recall that obesity is the result of an excess intake of calories over what we burn. Surplus calories, whether from carbohydrate, protein or fat, are stored as body fat. All food fats are a mix of unsaturated and saturated fatty acids; all provide the same number of calories per unit weight.

Saturated fats raise the risk of coronary heart disease, although not by much. Trans fats, banned in Denmark since 2003, are a greater risk factor. Because the different saturated fatty acids vary in their risk, imposing a single tax on them as if they are indistinguishable is difficult to support scientifically.

For these reasons, anti-obesity tax measures in other countries have tended to avoid targeting broad nutrient groups. Instead, they focus on processed foods, fast food or sugary drinks – all major sources of calories. Taxing them seems like a more promising strategy.

What else should governments be doing? That they have a role in addressing the health problems caused by obesity is beyond debate, not least because they bear much of the cost of dealing with such problems. In the US, economists estimate the cost of obesity-related healthcare and lost productivity at between $147 billion and $190 billion a year. The need to act is urgent. But how?

One lesson from Denmark is that small countries with open borders cannot raise the prices of food or anything else unless neighbouring countries also do so. But the greater lesson is that any attempt to encourage people to eat less will encounter fierce food-industry opposition. Eating less is bad for business.

In the US, state and city efforts to tax sugary drinks have met with overwhelming opposition from soft-drink companies. They have successfully spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying legislators and convincing the public that such measures deprive voters of their “right to choose” or, as in Denmark, can damage the economy.

What’s more, the poor cannot be expected to support measures that increase food costs, even though obesity-related problems are much more common among low-income groups.

If governments really want to reduce the costs of obesity-related chronic diseases, they will have to address the problem at its source: the production and marketing of unhealthy food products.

A review by the American Heart Association cites increasing evidence for the benefits of anti-obesity interventions: food taxes, subsidising healthy foods, media campaigns to promote exercise and good diet, restrictions on portion sizes, and restrictions on the marketing of unhealthy foods and their sale in schools.

Governments must decide whether they want to bear the political consequences of putting health before business interests. The Danish government cast a clear vote for business.

At some point, governments will need to find ways to make food firms responsible for the health problems their products cause. When they do, we are likely to see immediate improvements in food quality and health. Let’s hope this happens soon.

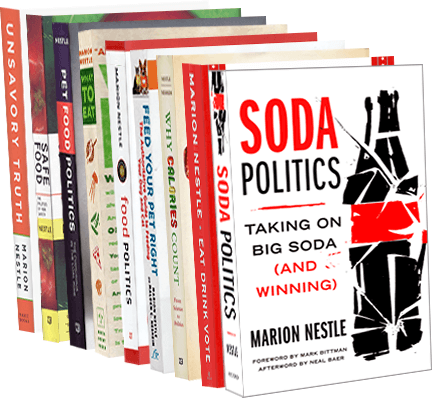

Marion Nestle is the author of Food Politics and What to Eat and is the Paulette Goddard professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University