USDA says it will try to reduce Salmonella in poultry. What about FDA-regulated onions?

In a press release, the USDA says it is going to take action against Salmonella contamination of poultry in order to get closer to the national target of a 25% reduction in Salmonella illnesses.

Despite consistent reductions in the occurrence of Salmonella in poultry products, more than 1 million consumer illnesses due to Salmonella occur annually, and it is estimated (PDF, 1.4 MB) that over 23% of those illnesses are due to consumption of chicken and turkey…USDA intends to seek stakeholder feedback on specific Salmonella control and measurement strategies, including pilot projects, in poultry slaughter and processing establishments. A key component of this approach is encouraging preharvest controls to reduce Salmonella contamination coming into the slaughterhouse.

The North American Meat Institute says its members are happy to assist (Salmonella is a problem for poultry, not beef).

The National Chicken Council also pledged to assist with the pilot projects, but then put the onus of responsibility squarely on you.

Even with very low levels of pathogens, there is still the possibility of illness if a raw product is improperly handled or cooked. Increased consumer education about proper handling and cooking of raw meat must be part of any framework moving forward. Proper handling and cooking of poultry is the one thing that will eliminate any risk of foodborne illness. All bacteria potentially found on raw chicken, regardless of strain, are fully destroyed by handling the product properly and cooking it to an internal temperature of 165°.

The newly formed Coalition for Poultry Food Safety Reform, led by Center for Science in the Public Interest, welcomes the USDA’s announcement, but insists that USDA’s food safety oversight needs to extend from farm to fork.

Comment: The USDA’s jurisdiction starts at the slaughterhouse, but chickens coming into the plant are already contaminated with Salmonella. This means prevention has to start on the farm, and poultry producers would have to institute procedures to keep their flocks free of Salmonella. They would much rather you cooked your chicken properly.

The latest big Salmonella outbreak is due to onions, an FDA-regulated food.

FDA’s traceback investigation is ongoing but has identified ProSource Produce, LLC (also known as ProSource Inc.) of Hailey, Idaho, and Keeler Family Farms of Deming, New Mexico, as suppliers of potentially contaminated whole, fresh onions imported from the State of Chihuahua, Mexico.

Keeler Family Farms issued a voluntary recall. ProSource Produce LLC also issued a voluntary recall.

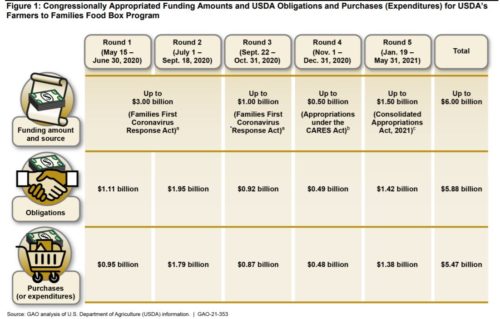

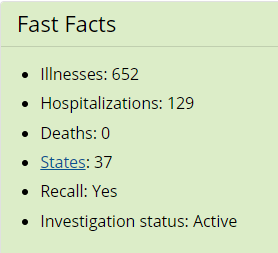

The CDC has the statistics:

Comment: I wrote about a previous onion recall last year. Food safety lawyer Bill Marler asks: What did we learn – or not – from the 2020 Salmonella Outbreak linked to onions? That investigation, as he emphasizes, identified probable causes:

- potentially contaminated sources of irrigation water;

- sheep grazing on adjacent land;

- signs of animal intrusion, including scat (fecal droppings), and large flocks of birds that may spread contamination; and

- food contact surfaces that had not been inspected, maintained, or cleaned as frequently as necessary to protect against the contamination of produce.

The FDA lists all the products that have been recalled so far. It also displays their labels. If you have onions from these companies, treat them like biosafety hazards. If you can’t bear to throw them out, at least boil them and sterilize everything they could have contacted.