My monthly, first Sunday column in the San Francisco Chronicle:

Q: I still don’t get it. Why would a city government think that a food regulation would promote health when any one of them is so easy to evade?

A: Quick answer: because they work.

As I explained in my July discussion of Richmond’s proposed soda tax, regulations make it easier for people to eat healthfully without having to think about it. They make the default choice the healthy choice. Most people choose the default, no matter what it is.

Telling people cigarettes cause cancer hardly ever got anyone to stop. But regulations did. Taxing cigarettes, banning advertising, setting age limits for purchases, and restricting smoking in airplanes, workplaces, bars and restaurants made it easier for smokers to stop.

Economists say, obesity and its consequences cost our society $190 billion annually in health care and lost productivity, so health officials increasingly want to find equally effective strategies to discourage people from over-consuming sugary drinks and fast food.

Research backs up regulatory approaches. We know what makes us overeat: billions of dollars in advertising messages, food sold everywhere – in gas stations, vending machines, libraries and stores that sell clothing, books, office supplies, cosmetics and drugs – and huge portions of food at bargain prices.

Research also shows what sells food to kids: cartoons, celebrities, commercials on their favorite television programs, and toys in Happy Meals. This kind of marketing induces kids to want the products, pester their parents for them, and throw tantrums if parents say no. Marketing makes kids think they are supposed to eat advertised foods, and so undermines parental authority.

Public health officials look for ways to intervene, given their particular legislated mandates and authority. But much as they might like to, they can’t do much about marketing to children. Food and beverage companies invoke the First Amendment to protect their “right” to market junk foods to kids. They lobby Congress on this issue so effectively that they even managed to block the Federal Trade Commission‘s proposed nonbinding, voluntary nutrition standards for marketing food to kids.

Short of marketing restrictions, city officials are trying other options. They pass laws to require menu labeling for fast food, ban trans fats, prohibit toys in fast-food kids’ meals and restrict junk foods sold in schools. They propose taxes on sodas and caps on soda sizes.

Research demonstrating the value of regulatory approaches is now pouring in.

Studies of the effects of menu labeling show that not everyone pays attention, but those who do are more likely to reduce their calorie purchases. Menu labels certainly change my behavior. Do I really want a 600-calorie breakfast muffin? Not today, thanks.

New York City’s 2008 ban on use of hydrogenated oils containing trans fats means that New Yorkers get less trans fat with their fast food, even in low-income neighborhoods. Whether this reduction accounts for the recent decline in the city’s rates of heart disease remains to be demonstrated, but getting rid of trans fats certainly hasn’t hurt.

Canadian researchers report that kids are three times more likely to choose healthier meals if those meals come with a toy and the regular ones do not. When it comes to kids’ food choices, the meal with the toy is invariably the default.

A recent study in Pediatrics compared obesity rates in kids living in states with and without restrictions on the kinds of foods sold in schools. Guess what – the kids living in states where schools don’t sell junk food are not as overweight.

Circulation has just published an American Heart Association review of “evidence-based population approaches” to improving diets. It concludes that evidence supports the value of intense media campaigns, on-site educational programs in stores, subsidies for fruits and vegetables, taxes, school gardens, worksite wellness programs and restrictions on marketing to children.

The benefits of the approaches shown in these studies may appear small, but together they offer hope that current trends can be reversed.

Researchers also suggest other approaches, not yet tried. The Yale Rudd Center has just shown that color-coded food labels (“traffic lights”) encourage healthier food choices.

And Rand Corp. researchers propose initiatives like those that worked for alcoholic beverages: Limit the density of fast-food outlets, ban sales in places that are not food stores, insist that supermarkets put junk foods and sodas where they are hard to see, ban drive-through sales, restrict portion sizes and use warning labels.

These regulatory approaches are worth trying. If research continues to demonstrate their value, cities will have even more reason to use them. If the research becomes compelling enough, the federal government might need to act.

In the meantime, cities are leading the way, Richmond among them. Their initiatives are well worth trying, testing and supporting.

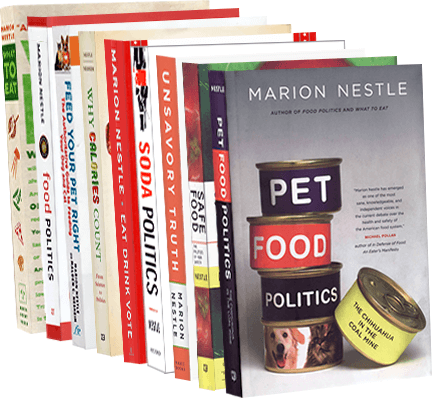

**Marion Nestle is the author of “Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics,” as well as “Food Politics” and “What to Eat,” among other books. She is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University, and blogs at foodpolitics.store. E-mail: food@sfchronicle.com